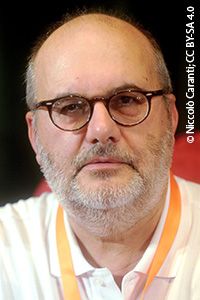

Interview with Branko Milanović: The privilege of being born in the "right" country

Branko Milanović: Yes, we try to determine how much it is worth being born to rich parents. We use the data on each country’s intergenerational income mobility – that is, the correlation between parental and children’s income classes. To see how this is done, suppose that a country has very little intergenerational mobility. In that case, people whom we currently observe in country’s top income class will have almost entirely come from parents who themselves belonged to high income classes. The opposite is true when there is high social mobility: then people whom we currently observe in top or bottom income classes will have come from parents randomly distributed along income distribution. In real life, countries will cover a vast spectrum between these two extreme positions. This gives, for a person that we observe today at a given position in income distribution, the part of his or her income that is due to family background. Another, generally larger part comes from being born in a given country. Rich countries provide what may be called “citizenship or location premium”, poor countries, “citizenship or location penalty.”

POLITIKUM: You use this data to show how much of a person's income is determined by birth. After all, one has no influence whatsoever on the social status of the parental home, just as little as on the second factor, the place of birth. In one of the texts of your book "The Haves and the Have-Nots" you therefore raise the question "How Much of Your Income is Determined at Birth?". How do you answer this question?

Branko Milanović: Using these two pieces of information, namely, family background and person’s place of birth, allows us to explain more than 80 percent of a person’s long-term income. The place of birth – or, more exactly, citizenship – is “fate” unless the person is able to move to a different country. The poorest Americans for example are better off than more than two-thirds of the world population. We could continue for a long time to give examples that show the importance of this factor. Only 5 percent of Cameroonians for example have a higher income than the poorest Germans. One’s income thus crucially depends on citizenship, which in turn means – in a world of rather low international migration – place of birth. All people born in rich countries receive a location premium; all those born in poor countries get a location penalty.

POLITIKUM: To summarize: This “citizenship premium” for those who are born in the “right” places, and a “citizenship penalty” for those born in the “wrong” places determines the status of an individual much more than “class”?

Branko Milanović: Yes. Historically the location element was almost negligible. In 1820 for example only 20 percent of global inequality was due to difference among countries. This is because income gaps between GDPs of rich and poor countries were small. England and the Netherlands, then the richest countries, had an income just three times as high as China and Ceylon, then the poorest. Today, the gap between (say) the United States and Congo is more than 150 to 1. Most of global inequality resulted in the past from differences within countries. It was class that mattered. Being “well-born” in this world meant being born into a high income group in a country. But that changed completely over the next century. The proportions reversed: by the mid-twentieth century, 80 percent of global inequality depended on what country one was born and on who were his or her parents.

POLITIKUM: And the remaining 20 percent, you mentioned?

Branko Milanović: The remaining 20 percent or less is therefore due to other factors over which individuals have no control, such as gender, age, race, episodic luck, and to the factors over which they do have control – effort or hard work. If you want to put things broadly, we could say that one-half of your income depends on the place of birth, one-fourth on family background (wealth and social status of parents), and the final one-forth on your age, race, work and episodic luck. “Episodic luck” means a simple luck of running into a friend who might give you a job, or winning a lottery. It does not have much to do with the so-called “luck” of birth.

POLITIKUM: So, your own performance is just an unimportant determinant? It seems to me that this contrasts strikingly with public awareness, especially in Germany: fairness of performance is an important value. So, in relation to our income, are we counting on our own merit, which in reality hardly plays a role?

Branko Milanović: Indeed, our data shows that the portion left for effort must be very small. Yes, one can try hard to improve one’s position in a given country, provided that the country has a tolerable income mobility between the generations. But these efforts may often have a minuscule effect on one’s global income position. Note that I am speaking here of one’s global position. A person in Germany may try through his effort to improve his position by climbing from (say) fifth decile to the eighth income decile. That is impressive—but not when you look at it from a global perspective. Even the fifth German decile is highly placed globally, and the movement from the fifth to the eighth is an improvement but would be hardly registered on the global scale.

POLITIKUM: So a person can hardly do anything to improve his position?

Branko Milanović: There are three ways in which people can improve their global income position. First one’s own effort. The effort or luck may push a person up the national position if his society “accepts” some income mobility. But this cannot, from a global perspective, play a large role because more than 80 percent of variability in income globally is due to circumstances given at birth (citizenship and parental wealth). So that route can, at most, yield very modest results.

And the effort argument does not carry much empirical weight, because we know that the number of hours worked (for a given occupation) is greater in poor countries, despite the fact that people are paid less there. When we compare the same occupations that involve the same or greater amount of effort in poor countries, we still find very large differences in real wages in different countries. Consider three occupations with increased levels of skill – construction worker, skilled industrial worker, and engineer – in five cities, two rich (New York and London) and three poor (Beijing, Lagos, and Delhi). The real hourly, that is, per unit of effort, wage gap between the rich and poor cities is 11 to 1 for the construction worker, 6 to 1 for the skilled worker, and 3 to 1 for the engineer. Note that in this study both the skill level and effort are the same across the five cities, and the study adjust for the differences in the price level. So the argument that people in rich countries are paid more because they work more or are more skilled can be soundly rejected.

POLITIKUM: And what are the other two ways to improve the global income situation?

Branko Milanović: The second way is that a person can hope that his country will do well: The country’s position will then move up along the global distribution, carrying as it were the entire population with it. If he is lucky enough that his own effort (movement higher up along the national position) is combined with an upward movement of the position of the country, he may substantially climb up in the global income distribution. This is the experience of many young Chinese today. They improve their relative position within the country, and on top of that the country improves its global position. They are thus carried forward by two forces. The opposite of course holds for people who manage to improve their own position by hard work, but their country does badly and they fall back globally.

Or – a last possibility – he might try to „jump ship”, that is, move from a poorer country to a richer one. Even if he does not end up at the high end of the new country’s income distribution, he might still gain substantially. Thus, one’s own effort, one’s country doing well, and migration are the three ways. But one most consider that the role a person’s effort plays is small. And since he cannot influence his country’s growth rate, so the only realistic alternative then remains is migration.

POLITIKUM: As far as migration is concerned, you have shown in your book "Global Inequality" that the physical barriers to the movement of people correspond to the places where the poor and the rich world are in close physical proximity.

Branko Milanović: Exactly. There is a fundamental contradiction at the heart of globalization as it exists today. In its broadest terms, globalization implies the seamless movement of the factors of production, goods, technology, and ideas across the world. But while this is true for capital, merchandise exports and imports, it is not true for labor. The stock of migrants globally, measured as a share of world population, did not increase between 1980 and 2010.

POLITIKUM: Your research results seem to shake central ideas about our society. In my opinion, they raise fundamental questions of justice and legitimacy - including one's own place in the world - which everyone should ask themselves. Thank you for these important insights into your work.

Branko Milanović: Thank you for your interest and the conversation.